Pocket Neighborhood Beginnings

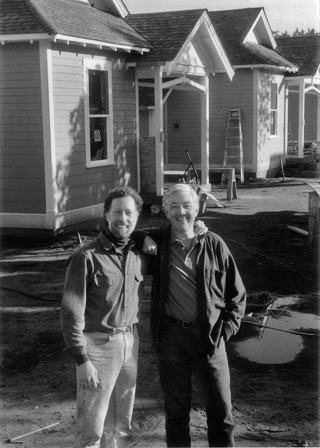

In 1996, architect Ross Chapin and developer Jim Soules collaborated on building the Third Street Cottages, a cluster of eight small cottages around a shared garden. The cottages were tucked off a busy street, which seemed to Ross like a pocket safely tucking away its possessions from the world outside. He began calling it a “pocket neighborhood”, and the term stuck.

The cottages had a very approachable style that everyone seemed to love. Yet beyond their appearance, it became immediately clear that they tapped a deep, unmet longing for community.

The cottages had a very approachable style that everyone seemed to love. Yet beyond their appearance, it became immediately clear that they tapped a deep, unmet longing for community.

Soon after the cottages were completed, word began to spread. The local newspaper ran the story, which was then picked up by the national press—appearing in over 200 newspapers, dozens of magazines, and TV programs across the country. The response was electric. People from all walks of life—single women, young families, empty nesters, and adults caring for aging parents—reached out asking for more communities like this. Planners, developers, architects, and community advocates also called, wanting to know: What kind of zoning made this possible? Who were the people living there? And how could pocket neighborhoods fit into their own towns?

In further joint-venture projects, Ross and his team at RCA and Jim Soules and Linda Pruitt with The Cottage Company continued to design and build variations of pocket neighborhoods to test the market around the Seattle area for these small-scale communities. At the same time, RCA began to design pocket neighborhoods for other developers around the country. Clearly, there was room for other approaches to housing than the single-family house on a private lot or attached condo.

Fine Homebuilding |

Taunton Press took notice as well, asking Ross to write an article about the Third Street Cottages for Fine Homebuilding Magazine. The next year, the project was featured in Taunton’s best selling book, Creating the Not So Big House, by Sarah Susanka.

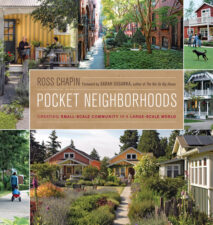

Taunton also approached Ross to write a book about pocket neighborhoods. Ross researched the pocket neighborhood idea and discovered a rich heritage of historic precedents, as well as a wide range of contemporary examples across America and around the world. He identified key design principles that helped to foster a sense of community, preserve household identity and privacy, and integrate into surrounding neighborhoods. He also came across many stories of ‘pioneers’ who imagined and built “living” communities. Much of this information made its way into the book, “Pocket Neighborhoods: Creating Small Scale Community in a Large Scale World”.

Taunton also approached Ross to write a book about pocket neighborhoods. Ross researched the pocket neighborhood idea and discovered a rich heritage of historic precedents, as well as a wide range of contemporary examples across America and around the world. He identified key design principles that helped to foster a sense of community, preserve household identity and privacy, and integrate into surrounding neighborhoods. He also came across many stories of ‘pioneers’ who imagined and built “living” communities. Much of this information made its way into the book, “Pocket Neighborhoods: Creating Small Scale Community in a Large Scale World”.

During the four years of research and travel for the book, I came to understand that pocket neighborhoods are not a new idea. They have deep and diverse roots—preceded by the bungalow courts of Southern California in the 1910s, East Coast summer church camp communities from the 1840s, Dutch hofje almshouses from the 15th to 18th centuries, and Chinese tulou courtyard buildings dating back to the 12th century. Similar patterns are found in traditional African multi-family villages, Norwegian collective farm clusters from as early as 300 A.D., and the communal longhouses of the Haida people along the Canadian Pacific Coast. The pocket neighborhood building type transcends time and culture, arising again and again from our inherently sociable human nature.

| GOOD WORDS |

—BEN BROWN, principal of Placemakers; former senior editor, USA Today

—JOHN NORQUIST, former CEO, Congress for the New Urbanism

—DAN BURDEN, director, Walkable and Livable Communities Institute

—MICHAEL MCKEEL, developer

—ELLEN DUNHAM-JONES, author, “Retrofitting Suburbia”

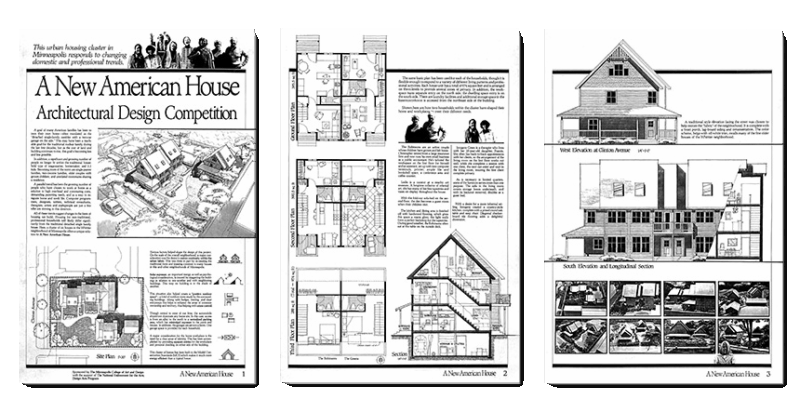

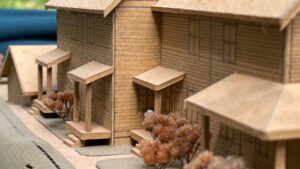

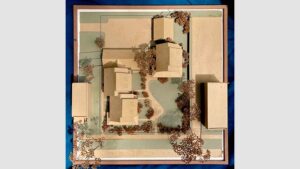

In 1984, Ross submitted a project to the New American House competition, sponsored by the Minneapolis College of Art and Design with support from the National Endowment for the Arts. The entry—awarded a merit prize—proposed a forward-thinking alternative to the traditional single-family house. Many of the themes it explored have since become central to the pocket neighborhood movement.

At the time, the standard dream of a detached house with a two-car garage was becoming out of reach for many. But more importantly, that model no longer fit the diverse realities of American households: two-income couples, single parents, empty nesters, and unrelated adults sharing homes. Work-from-home professionals were also on the rise—people seeking to blend living and working in ways that supported both.

The design proposed a small cluster of six townhomes in Minneapolis’s Whittier neighborhood. Each unit was compact, flexible, and designed to support a mix of personal and professional life—with separate entrances for work and home. Shared outdoor space created a sense of community and safety, while garages were tucked away to keep cars from dominating the setting. Thoughtful attention was given to solar access, neighborhood continuity, and a balance of privacy and connection.

It was an early expression of what would later be called a “pocket neighborhood”—and a step toward reimagining how we live together in a changing world.