Langley, a rural town of 1100 people on Whidbey Island, Washington, hosts a robust population of rabbits that have attracted national news. The deer population may not be as noteworthy, but they are common sight around town nibbling apples from trees and grazing lawns. Gardeners erect seven-foot-high fences to keep them out.

Langley, a rural town of 1100 people on Whidbey Island, Washington, hosts a robust population of rabbits that have attracted national news. The deer population may not be as noteworthy, but they are common sight around town nibbling apples from trees and grazing lawns. Gardeners erect seven-foot-high fences to keep them out.

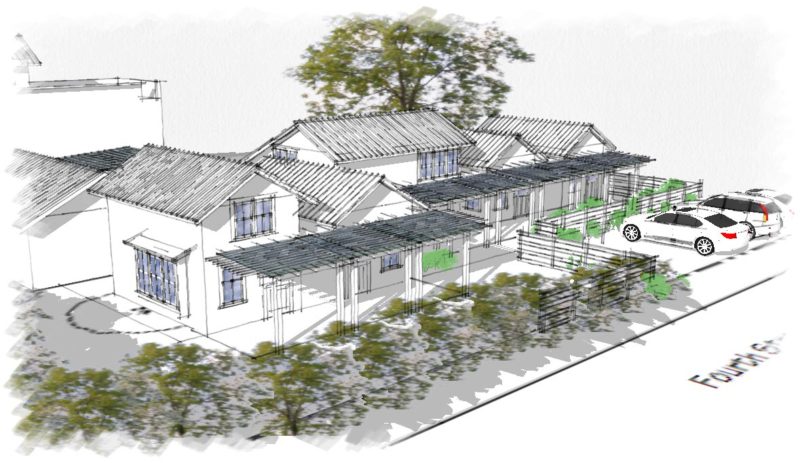

When we created Fifth Street Commons, a multi-generational community of 16 households, residents were all for vegetable gardens, fruit trees and flowers (deer’s delight!), which meant tall fences were needed all around, as well as gates between the parking area and the commons.

Fence solutions are straight forward, but gates pose numerous challenges: they are a hassle to navigate while carrying bags; they should open both ways for ease of movement; they should be self-closing if possible (otherwise, you can bet they will be left open just when deer make their rounds); and because they are used every day to welcome residents and guests, they should be beautiful.

In our case, we had an additional factor: the gates would have to span across existing five-foot-wide concrete walkways, which seemed awkwardly wide. As we explored solutions, we thought into ways to reduce the gate width: cutting a hole in the concrete to place a gatepost for a narrower opening (complicated and messy); fabricating a metal extension to a narrower pivot point (complicated); or letting go of a narrower gate and just living with the width as it is.

We went to the hardware store to look at two-way latches and spring closers (not satisfying). Online searching didn’t help much.

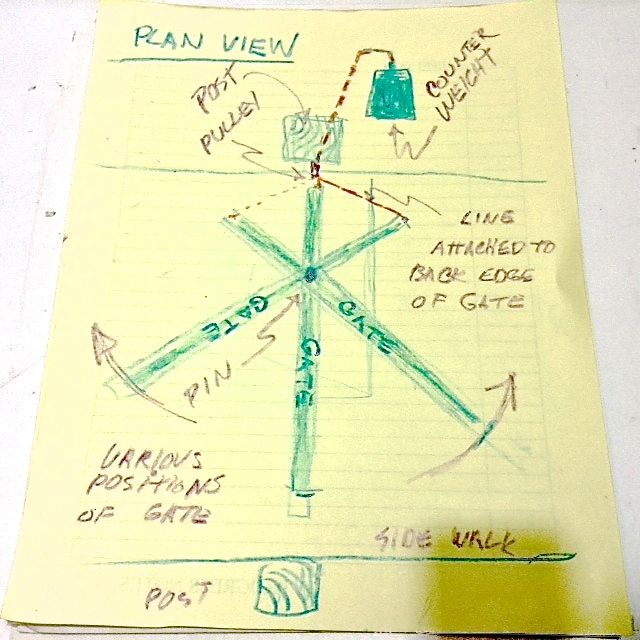

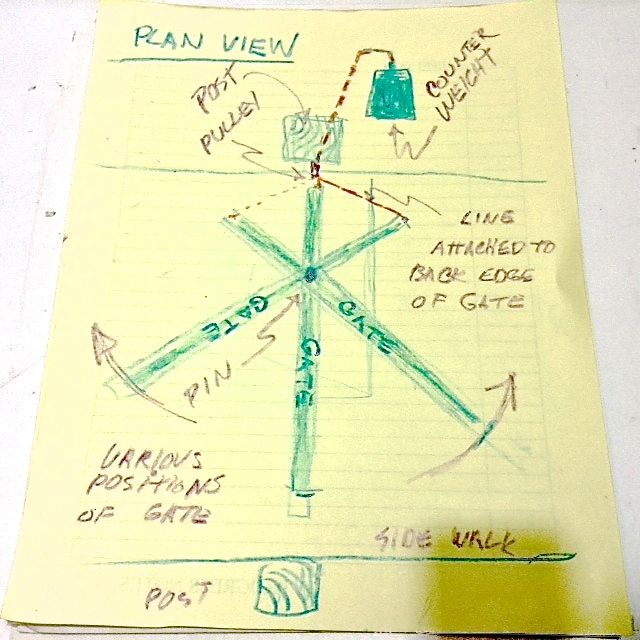

My friend Jay Davenny made a sketch of a gate he’d seen that pivoted at about the 1/3 point of a gate. It had a cord attached to the back edge of the gate that went over or through a side post to a counter-weight, which somehow pulled the gate shut. Seemed intriguing. I sketched my own versions trying to understand the details.

My friend Jay Davenny made a sketch of a gate he’d seen that pivoted at about the 1/3 point of a gate. It had a cord attached to the back edge of the gate that went over or through a side post to a counter-weight, which somehow pulled the gate shut. Seemed intriguing. I sketched my own versions trying to understand the details.

JR Fulton, my partner on FSC, said that he had some surplus solid stainless steel bars that we might use for the pivot axis. The possibility of an elegant solution seemed to be getting warmer.

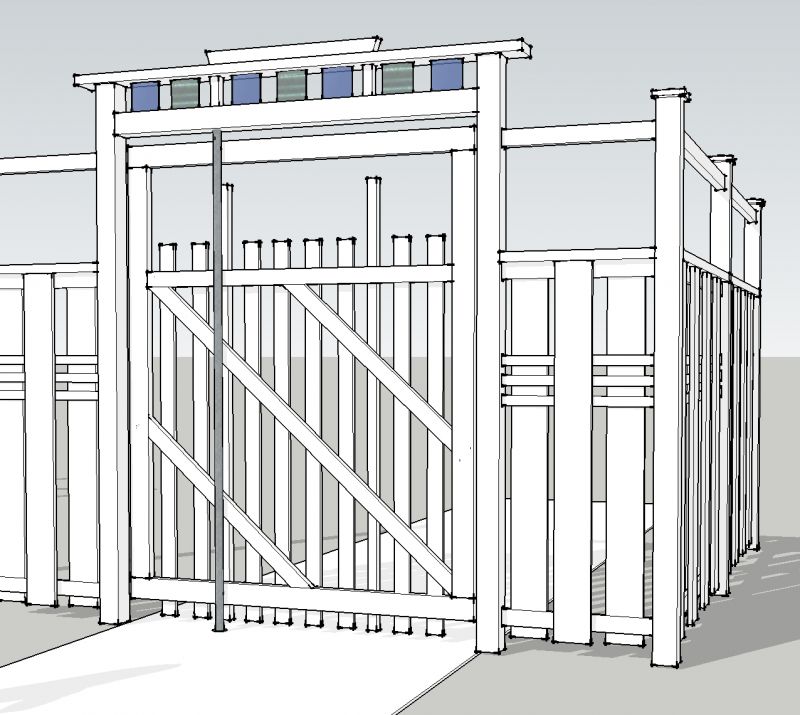

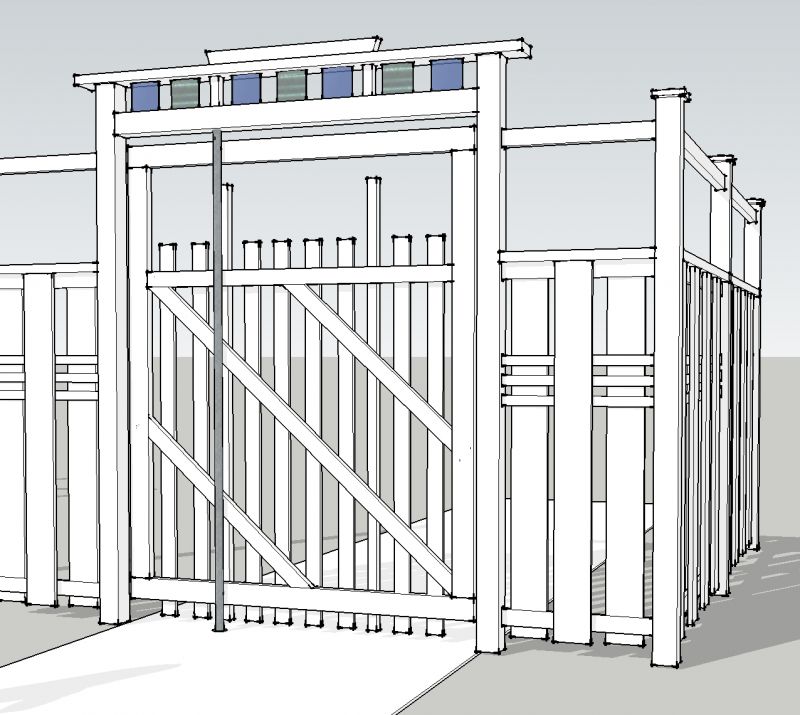

I drew a 3-D SketchUp model to visualize the gate design and details.

I searched online hardware suppliers and machine shop outlets for a rotating bearing base to receive the steel bar and anchor it into the concrete. I’d never seen such a thing, but it had to exist! It needed to fit the bar exactly. Tenacity and persistence drove me to keep searching. I’m a little embarrassed to say how long I stayed at it, but in the end, I found the precise item: a “1.25-inch three-bolt flange bearing” for $15.67 (cheaper in bulk).

For the cord system, I figured we could run the line directly through the side post at the narrow end of the gate, but we needed some kind of gasket or grommet to reduce friction as the line pulled one way then the other at the opening. More searching. At this point, I was getting very familiar with marine rigging suppliers. I found something called a “fairlead thru-deck bushing” to do the trick. And at the local hardware story I found a plastic pipe clamp to guide the line out and down on the far side of the post, reducing the angle of pull on the opening.

So far, so good. We set out to construct the gate, starting first with 4×4 pressure-treated posts and top beam. This wood isn’t the most aesthetic choice, but it resists rot and is reasonably  priced. The wood for the gate frame is made with cedar. We located the position for the pivot bar base, drilled holes in the concrete to receive the flange bolts and set the mechanism in place with epoxy. We left it to harden overnight, and went on to securing the pivot bar to the gate frame and drilling a hole in the overhead beam to receive the top end of the bar.

priced. The wood for the gate frame is made with cedar. We located the position for the pivot bar base, drilled holes in the concrete to receive the flange bolts and set the mechanism in place with epoxy. We left it to harden overnight, and went on to securing the pivot bar to the gate frame and drilling a hole in the overhead beam to receive the top end of the bar.

The idea for the self-closing action of the gate is that a counter weight attached to a cord through the post to the short end of the gate would pull it to a closed position from both directions. For the weight, I found an iron bar used in old-style single-hung windows at the local recycling center.

The moment of truth came when we put all the elements together. Would it work? … Well, sort of. The counterweight was way too heavy, causing a lot of effort to push the gate open. We replaced it with a 3-lb demolition hammer, which made the push easier, but it was still too heavy. A carpenter’s hammer was not heavy enough, but with it we realized that the sweet spot was close.

The moment of truth came when we put all the elements together. Would it work? … Well, sort of. The counterweight was way too heavy, causing a lot of effort to push the gate open. We replaced it with a 3-lb demolition hammer, which made the push easier, but it was still too heavy. A carpenter’s hammer was not heavy enough, but with it we realized that the sweet spot was close.

Our Goldilocks solution came from the recycle bin: a plastic soda bottle, filled with water. We drilled a hole through the cap, ran the cord through it, tied a knot and put the cap back on. With a bit of trial and error we found just the right amount of water as a counterweight to gently pull the gate closed and provide light resistance in opening. Voila! Simple, a pleasure to use, and in it’s own way, beautiful.

— Ross Chapin

As I fly back to Minnesota to be with my family for Thanksgiving, I think about looking out on the lake I grew up next to. At this time of year, the last leaves have fallen, the temperatures drop into the 20s and everyone is anticipating the first ice on the lake. Overhead, geese are flying south.

As I fly back to Minnesota to be with my family for Thanksgiving, I think about looking out on the lake I grew up next to. At this time of year, the last leaves have fallen, the temperatures drop into the 20s and everyone is anticipating the first ice on the lake. Overhead, geese are flying south.

Langley, a rural town of 1100 people on Whidbey Island, Washington, hosts a robust population of rabbits that have attracted

Langley, a rural town of 1100 people on Whidbey Island, Washington, hosts a robust population of rabbits that have attracted  My friend Jay Davenny made a sketch of a gate he’d seen that pivoted at about the 1/3 point of a gate. It had a cord attached to the back edge of the gate that went over or through a side post to a counter-weight, which somehow pulled the gate shut. Seemed intriguing. I sketched my own versions trying to understand the details.

My friend Jay Davenny made a sketch of a gate he’d seen that pivoted at about the 1/3 point of a gate. It had a cord attached to the back edge of the gate that went over or through a side post to a counter-weight, which somehow pulled the gate shut. Seemed intriguing. I sketched my own versions trying to understand the details.

priced. The wood for the gate frame is made with cedar. We located the position for the pivot bar base, drilled holes in the concrete to receive the flange bolts and set the mechanism in place with epoxy. We left it to harden overnight, and went on to securing the pivot bar to the gate frame and drilling a hole in the overhead beam to receive the top end of the bar.

priced. The wood for the gate frame is made with cedar. We located the position for the pivot bar base, drilled holes in the concrete to receive the flange bolts and set the mechanism in place with epoxy. We left it to harden overnight, and went on to securing the pivot bar to the gate frame and drilling a hole in the overhead beam to receive the top end of the bar. The moment of truth came when we put all the elements together. Would it work? … Well, sort of. The counterweight was way too heavy, causing a lot of effort to push the gate open. We replaced it with a 3-lb demolition hammer, which made the push easier, but it was still too heavy. A carpenter’s hammer was not heavy enough, but with it we realized that the sweet spot was close.

The moment of truth came when we put all the elements together. Would it work? … Well, sort of. The counterweight was way too heavy, causing a lot of effort to push the gate open. We replaced it with a 3-lb demolition hammer, which made the push easier, but it was still too heavy. A carpenter’s hammer was not heavy enough, but with it we realized that the sweet spot was close.

Small houses are getting a lot of

Small houses are getting a lot of  Ben Brown of PlaceMakers, who lived in a 308-square-foot

Ben Brown of PlaceMakers, who lived in a 308-square-foot

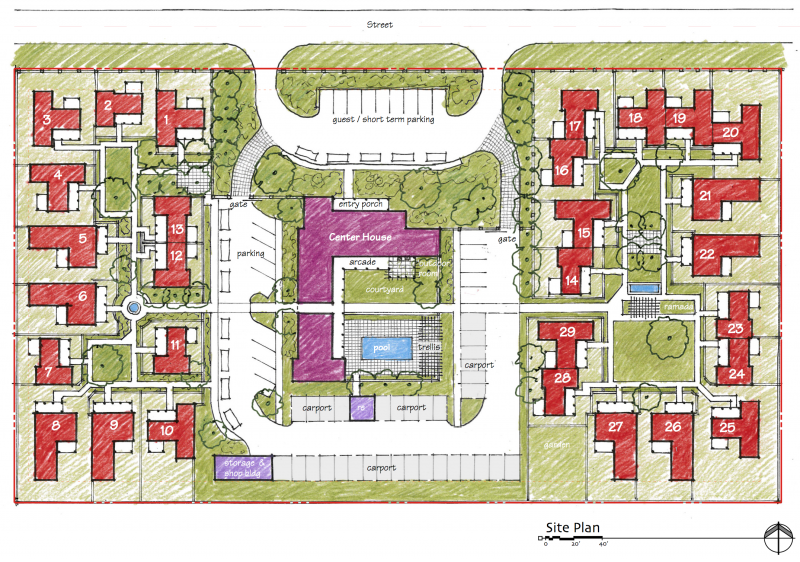

The site Roth has chosen is in the Phoenix metro area—a very different climate condition and cultural heritage than most sites we work with. For this, we’ve developed vernacular design elements and materials familiar with the region. We’re incorporating deep arcades, trellised ramadas and fountains. Fundamentally, though, the community includes many of the

The site Roth has chosen is in the Phoenix metro area—a very different climate condition and cultural heritage than most sites we work with. For this, we’ve developed vernacular design elements and materials familiar with the region. We’re incorporating deep arcades, trellised ramadas and fountains. Fundamentally, though, the community includes many of the  Holding the center between two clustered pocket neighborhoods (30 dwellings total) is the Center House, with community gathering spaces, exercise center, offices, and guest spaces. In the courtyard will be a pool and patio, covered outdoor room with a fireplace, and lawn.

Holding the center between two clustered pocket neighborhoods (30 dwellings total) is the Center House, with community gathering spaces, exercise center, offices, and guest spaces. In the courtyard will be a pool and patio, covered outdoor room with a fireplace, and lawn. The housing clusters, while similar, are laid out with differentiating elements. For spatial clarity, especially for residents with autism, a central linear walkway ties the pocket neighborhoods through the Center House.

The housing clusters, while similar, are laid out with differentiating elements. For spatial clarity, especially for residents with autism, a central linear walkway ties the pocket neighborhoods through the Center House.